1

I do my best to hide the pain.

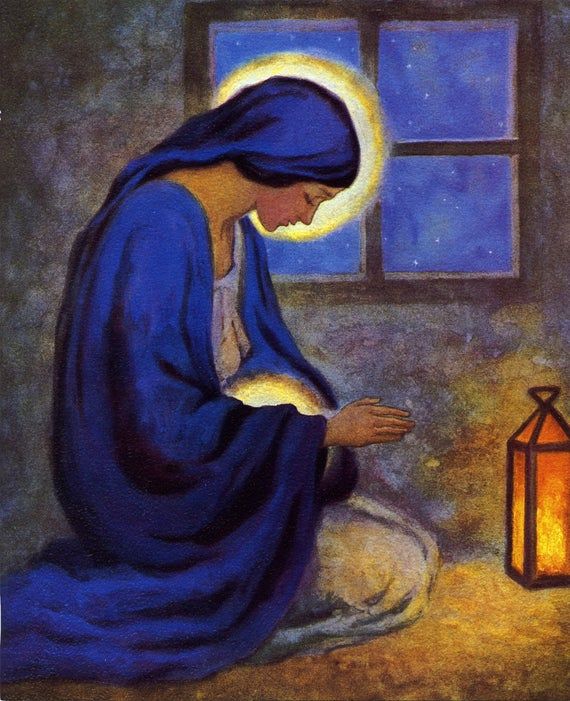

The little house is crowded. With the relatives in town, there is hardly a place to sit, let alone a private room or a bed to oneself. I share with Yosef’s younger sisters, but at night I must turn about constantly. Eventually, one of the sisters takes hold of a blanket and moves to the floor, not far from where her brothers sleep. This morning, I wake with an aching back and an odd cramping pain that flares up at random. Throughout the day, I bite my lip, trying not to show how uncomfortable I am.

Lately, the baby seems completely uninterested in sleep. He moves about my womb with a great, bouncing restlessness. The women of the house say he’s eager to be born, that he’s impatient to meet everyone. One of the sisters wonders aloud if all the kicking and shifting means he’ll be a handful to raise. I feign a laugh, but I’m wondering the same thing. The child’s abiding energy unnerves me.

I count it a grace that the women even indulge my presence. None of this has come easily for them either. I don’t begrudge the forced kindness in their tones, or the way they maintain a slight distance from me most of the time. Occasionally I’ll turn my head and catch one of the sisters quickly averting her stare. It’s to be expected. Here in the southern lands there are less whispers, but whispers nonetheless. These women may trust Yosef, but that doesn’t mean they’ll ever fully trust me.

It’s difficult not to have Yosef nearby. Everyone is more gracious when he’s around. He has a calm and quiet way. Without saying a word, he can evoke goodness and courtesy from an entire household. But he doesn’t linger in the house. When the morning sun gilds the eastern hills, he’s out the door, his purse thrown over his shoulder and weighed down with tools. The better part of each day he gives to the community – repairs their lentils, patches their roofs, restores the walls in their homes that have begun to crumble. Like his father before him, Yosef is an agent of renewal for this village that has watched him come of age. And now, with the census, there’s more work to be done, more people to shelter, more mouths to feed.

The odd morning pain has increased. It no longer seems random, nor does the discomfort abate for long. I try to mask it, try to turn my winces into smiles. My heartbeat quickens. I know what’s happening, and I’m afraid.

Not now. Not yet.

Some evenings, Yosef eats with those whose homes he has serviced that day. The others, he appears only briefly, hardly long enough to dip a hunk of bread in the stew and chew, before withdrawing again to the ongoing project outside. From where I sit now, furtively breathing through the contractions, I can hear them on the other side of the house wall – Yosef and his younger brother scraping and packing and grunting from the weight of the materials, and the short statements from their father, Yakov, whose knotted, shaking hands have long-since precluded him from work, but who still points trembling knuckles and offers experienced advice. It is slow work, and now I worry it has been too slow. My throat lumps, and tears push against the back of my eyes. After all, it’s my fault the room hasn’t been finished. Yosef is more than a capable builder, but because of all that has happened, and the way it has happened, he hasn’t had enough time to complete the job.

Yet it seems HaShem has completed his.

2

“Are you all right, child?” Yosef’s mother is gazing up at me from the bottom of the stairs that lead to the lower level of the house. She has been lining the mangers with hay. Behind her, the sisters lead the animals inside for the night – a goat and two ewes freshly sheered, one of which carries a lamb of her own. She walks slower than the other, bleating meekly as she’s jostled inside. I know how she feels.

“I’m fine.” The old woman eyes me carefully. “It’s just… just the baby moving again. There’s no room.”

“Sounds to me like there’s plenty of room,” she replies.

The sisters finish shooing the animals to the troughs. Their mother hands a large clump of hay to one of them to take to the work ox, which is tied up outside – a shared possession among the neighbors. The dog trots inside as well and takes his place at the foot of the stairs. Yosef’s mother closes the door, then steps deftly over him and ascends the three steps to the main level. She meets my eyes and continues. “To be moving about like he is, there must be room enough.”

I nod. A tremor rattles. I exhale nervously. I know Yosef’s mother has been keeping watch over me. She’s nothing if not perceptive. I squeeze my eyes shut and try to conjure peaceful thoughts.

The one that comes to my mind – that has sustained me even as my anxieties have swelled – is the image of Yosef stepping across the threshold. Not the threshold of this house, but rather my father’s house.

Only four months ago, he turned from me. I had begun to show, and the rumors were spreading. Our confrontation was inevitable. I told him everything, as bewildering a tale as I knew it would be. The more I said, the more those expressive eyes of his flared with stifled fury and humiliation. Of course they did! How do you describe something like that and not sound utterly mad? His warm expression grew cold as he listened. His lips were set like a seal, locking in all emotion. Then my father sent me out of the room, but even from the courtyard I could hear their tense conversation, the shock and frustration in Yosef’s voice. I knew something had been broken. Like water from a cracked well, his trust was draining away.

I didn’t expect to see him again. No one did. But now, in my mind’s eye, the scene unfolds anew, and for a few moments it calms my nervous breathing. I see Yosef at the door of my father’s house, not a month later. His hands are clasped in front of him as he steps inside and removes his sandals. I watch, my heart in my throat, as he kneels in front of my father and asks his mercy. Then I am left open-mouthed when he does the same to me. “Forgive me,” he whispers. “I didn’t know. I didn’t understand.” I want to cry and laugh and speak all at once. I want to tell him that I hardly understand it either. I want to ask him what has changed, why has he returned? But I have no words. Here he is, back in Nazara, back in the home that scorned him, and he is on his knees like a chastened sinner, deferring to me. “Forgive me, Miriam,” he says, and the only response I am capable of is to reach out and take his hand in mine.

I’ve clung to that hand ever since.

3

“When do you think they will finish?” one of the sisters asks as the goat and the sheep nose eagerly at the hay in the mangers. The other sister is about the work of preparing the house for another crowded sleep – spreading blankets on the berths and the floor. Outside, scraping sounds testify that mortar is being spread. Incrementally, the walls grow. Just a few more days is all Yosef needs to finish it. I imagine the privacy such a room could offer. If only it were already finished.

“Soon enough,” Yosef’s mother answers.

“Will someone be able to sleep there?”

“Of course,” the older woman answers. “But not until after the ceremony.” She unfurls a blanket and spreads it below the bed I’m to sleep on. A few feet away, Yosef’s youngest brother is already asleep, snoring loudly. Yosef’s mother surveys the room, a grimace on her face. I know she recognizes how small the house has become. She doesn’t let on, but her concern for the new room to be completed is as heightened as mine. She tosses a fleeting look in my direction, evaluating me with a glance. I try to keep my composure, but I’m sweating now. I wonder if she is aware that time is up. The room is not finished, and there is no place available inside either. No suitable space for what is about to happen.

She turns away to fetch another blanket. That is when I double-over as another wave of pain rolls through me. Gripping the edge of the table, my fingernails dig into the rough wood.

“Will the ceremony be… before…?” Yosef’s sister falls silent. From across the candlelit room, she sees.

“Let’s not discuss it right now,” says her mother softly. Then her eyes catch sight of her daughter’s gaze, and she whirls to look at me again.

4

Before anyone can speak a word, the door to the house opens and in steps Yosef’s father, brother, and, finally, Yosef himself. Chilled night air billows in behind them. Yakov walks right past me, shedding his cloak. “It’s started raining,” he announces with disappointment. “Not long, I reckon, but we’ll have to take a break for now.”

Yosef’s mother ignores her husband. She rushes past him and both brothers to kneel at my feet. She lays her hand on my shoulder. “Are you all right, child?”

“Miriam?” Yosef’s soft voice is tinged with concern.

I hardly want to move for fear I’ll make the pain worse. My face contorts. This newest wave is horrible. Is it supposed to feel like this?

“Breathe, my dear,” says the old woman, taking my hand. “Breathe long and slow.”

“I can’t… there’s no…”

“Don’t speak. Breathe.”

“But there’s no…”

“Just breathe.”

A shudder overwhelms me, from my shoulders down to my feet. My jaw tightens. I want to speak, to raise a protest – I can’t have this child here! There’s no room! – but my body won’t allow it.

“Breathe, Miriam,” she urges. “It helps to breathe.”

“What can I do?” The inquiries come from all directions, from Yosef’s brother, from Yakov, even from the younger one who, in the suddenly tense and crowded house, has sat up rubbing his eyes.

One of the sisters rushes forward and crouches next to us. “Fetch a basin and as much clean cloth as you can find,” her mother commands. Through squinting eyes, I see her gaze pass over the room once more. Her brow is furrowed. She looks dissatisfied, disappointed. I want to apologize, to tell her how sorry I am, sorry for what I’ve done to their family, for the turmoil I’ve caused, but I’m still paralyzed by the contractions.

“Mother,” says Yosef, kneeling on the other side and taking hold of my other hand. I immediately squeeze it, and won’t let it go.

“Don’t fear, my son,” she says, but she doesn’t look at him. She is still considering the room.

“It’s not finished,” he tells her. “The walls, or the roof. And it’s raining.”

Red-faced, I suck in breath. A moan escapes my clenched throat.

“I know,” Yosef’s mother whispers. “We need space and privacy. There are too many people in this house!”

Finally, the intensity lessens, and I release a long, ragged breath. Tears immediately follow. My shoulders tremble with sudden, uncontrollable sobbing.

Yosef places his other hand over mine. “Miriam, it’ll be-”

“Draw some water,” his mother interrupts, “and heat it. Quickly.”

“No!” I cry as Yosef stands up. I can’t bear him leaving my side.

“Don’t be afraid,” she tells me, taking hold of my hand and working it free. She is surprisingly strong. Yosef hurries away. His brother frantically stokes the hearth fire. “I want you to try to stand up,” she says softly. She’s come around and is already lifting me from the chair.

Somehow, I gain my feet. My knees shake. Where are we going?

Yosef’s mother looks for her other daughter, finds her standing frozen at the foot of the lower level steps, eyes as full and wide as the moon. “Put the animals out,” she says abruptly. “And bring in more straw.”

“But… but where is she going to…”

“Don’t stand there blubbering, girl! Do as I say. We need room, however we can get it.”

“My dear,” Yosef’s father says. “The stall?”

Still holding me tightly, she turns to her husband. “Yes, Yakov. The stall.”

I’m hit again. Unable to hold back a scream, I collapse against the old woman, but she keeps me upright. “Breathe, child. Breathe.” Then she looks back to her husband. “If there’s no room, then we’ll have to make room. Help us down these steps, and then go give word to the women. Tell them where to find us.”

“Mother,” says Yosef’s brother. “Let me go to the neighbor’s and ask if we might-”

“Enough of that,” the old woman insists. “We’ll not be shooing this poor girl all over Bet Lehem. She is in no condition for it. The stall will do. What matters is the child. Now, be silent and fetch some blankets.”

Yosef’s mother is practically carrying me, an astonishing feat for a woman of so small a frame. Her daughter frantically shoves the animals away. The dog scampers back, and the pregnant ewe gives an irritated bleat as she waddles back through the stall door and into the courtyard. Yakov, soon to become my father, somehow keeps the two of us balanced with his palsied hands. We slowly descend the wooden steps to the dusty, straw-laden floor. The smell of musk, hay, and excrement greets my nose. Nausea floods through me.

“I can’t,” I tell them. “It can’t be here.”

A voice behind me, confident and calming, says, “It will be all right, Miriam. I’m here. I’m going to stay by your side.”

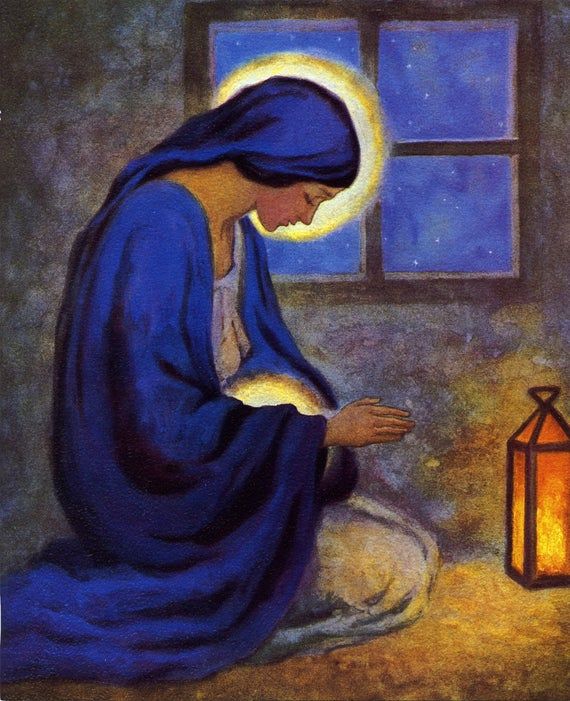

“Don’t be afraid, child,” his mother whispers in my ear as we shuffle toward the rear stall, as private a spot as can be found in the little house. “I know it’s not the way you wanted or the way you expected, but even in such a place as this, HaShem is with you. He is with us all. You’re not alone. You’ve never been alone.”

_resources1_16a0854053b_large.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9160067/Pumpkin_Spice_Latte___2015__4_.jpg)