Have you ever prayed to become a better Christian?

Well, stop it.

There’s no such thing.

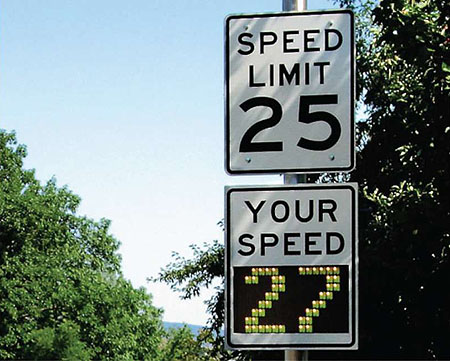

Some believers are under the impression that a relationship with Jesus is meant to be an ever-increasing advancement – that the Christian life contains higher levels of capability and competence, like promotions within a corporation, and if we would just show up early, put in the work, and leave late, eventually we will climb the spiritual ladder. The worst part of this misconception is that a lot of new believers think that Christians who have attained these alleged higher levels don’t have to deal with the temptations and struggles that rage down in the mailrooms and custodial closets of faith. Up in the corner offices of Christianity are those who sit above all that stuff.

While it is certainly true that we are meant to mature in our faith – to grow more trusting and find deeper reservoirs of strength – a relationship with Jesus is not about promotion. There is no such thing as “a better Christian.”

There are days when you may feel like you’re sitting high in that corner office of unchallenged commitment, but watch out, because before you know it, you may find yourself back down in the basement aimlessly sorting mail.

The misconception in Christianity that we can attain higher levels of faith is born out of a fear of failure. We don’t like to back-slide, to spurn our commitments and indulge in selfishness. So, we convince ourselves that there is some Rubicon within the Christian life – a point of no return that, if we can live obediently enough to reach it and cross it, we will never have to return to the laborious, unpredictable days of unripe belief.

“Actually, the crossing of the Rubicon signaled the start of conflict, not the end of it.” – the Metaphor Police

Of course, this belief drags several problems along with it. The first is that we can end up lying to ourselves about our spiritual health. If I believe in higher levels of the Christian life where fledgling struggles and beginner’s temptations no longer affect me, when those trials inevitably rear their heads, I may feel I need to pretend I’m not influenced by them. And, if I don’t end up lying to myself, then another problem I may encounter is self-devaluation. I will take my inevitable missteps and failures as proof that I’m incapable of attaining the higher levels, and will begin to hate myself (rather than hating only my sinful nature). Christians who continually deprecate themselves in their prayers and testimonies will find it very hard to accept the unconditional love of God.

But sometimes the biggest problem for people who believe faith is like a corporate ladder is that they can develop a sense of entitlement. If I am disciplined and obedient (to whatever predetermined extent), I deserve ______ from God. Some will fill that blank with recognition. Others, with particular blessings. Whatever it is, they unwittingly make God’s provision obligatory.

Several years ago, I found myself caught up in the throes of this third problem. So certain was I in the foolproof formula of a traditional quiet time that I truly believed my keeping it would rocket me upward into the stratospheres and ionospheres of faith. Maybe not right away – rocket boosters have to burn for a few moments before you see movement – but once I got going, “Houston, we have liftoff.”

But that feeling of incompetence continued, and after weeks and even months of seeing little difference in my attitudes and actions, I began to get angry. Angry at myself, but also angry at God. Couldn’t he see that I was trying? Didn’t he realize I was attempting to discipline myself? Why was he still standing far off? I was the lost son returning home – why wasn’t he running out to embrace me? Where was the party? Where was the fatted calf?

The only thing I knew to do, and was counseled to do by various church leaders, was to keep at it. God would show up, eventually. Read those Psalms, they told me; those folks had to wait on God, too, and they kept right on praying and praising.

And so, for years, I believed that strict adherence to a specific quiet time method would eventually result in some kind of breakthrough. I would wake up one day and my prayers would flow like a mountain river, the words of 1st Chronicles would suddenly become life-giving, and every sentence I wrote in my journal would be more profound than the last. Life itself would reverberate with meaning. Things would finally be easier. I would have reached that corner office, and all my present struggles and feelings of discontent would seem so small, so very, very far away. But that breakthrough never came.

Why?

Because my daily quiet time had morphed into devotion to a system rather than devotion to a Savior.

Without meaning to, I had become a Pharisee.

The if-you-will-do-this-then-God-will-do-that system of thought comes up time and again in Scripture, and time and again people get it wrong – the most famous example being the Pharisees of first-century Judaism. These people were the most influential sect of teachers, scribes and lawyers, and the ones who seemed to clash most often with Jesus. We often criticize the Pharisees for being legalistic and close-minded, and yet they appear to be the closest comparison to Christians in America today. In reality, among the people of the first-century, Pharisees were the most faithful students of the Scriptures. They were devoted to prayer and theological reflection, and they were adamant about the importance of an obedient lifestyle. Some of the most famous and gifted rabbis ever to arise in early Judaism were Pharisees.

The Pharisees believed strongly in the if/then promises of the Torah, and were careful to faithfully keep the “ifs” so that God might follow through with the “thens.” Several times, Jesus pointed out the main problem with this. The Pharisees had lost sight of the goodness of God, particularly the fact that he was even willing to offer promises to human beings at all. In so doing, Jesus informed them that they had fallen out of a real relationship with the God they so desired to please.

The irony was that the Scriptures – which they knew better than anyone due to such rigid devotional methods – are replete with reminders that what God is after is not a process, but a posture. In Psalm 51, David prays, “For you will not delight in sacrifice, or I would give it; you will not be pleased with a burnt offering. The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.” Long before Jesus came on the scene, the prophet Hosea bore witness to a sacrificial/devotional system that had lost all meaning, stating the people’s worship was “like the morning mist, like the early dew that disappears,” to which God responds, “I desire mercy, not sacrifice, and acknowledgment of God rather than burnt offerings.” In Matthew 9, Jesus tells the Pharisees they ought to take another look at Hosea, because no matter how ironclad the process might be, transformation is impossible without the right posture.

The Pharisees believed that God owed them something – that their status as God’s chosen people was not only based in history, but also sustained by their faithful keeping of the Torah. They believed their rigid loyalty to the Law of Moses had caused them to attain the higher levels. And so, they lived as if they resided in those corner offices of the faith. Jesus was disgusted with this sense of entitlement, as well as the fact that the Pharisees so often made life difficult for the mailroom clerks and custodians just trying to make ends meet spiritually. Those who had seemingly mastered obedience made no effort to help others with it.

There is no such thing as becoming “a better Christian.” And when it comes to quiet times, the most dangerous thing you can do is become a slave to a formula, believing dogged tenacity will accomplish the kind of spiritual growth you’re hoping for.

I will continue this series next week with an argument for why the traditional formula itself is faulty. However, may we be mindful of our motivations when we seek communion with God. In the same spirit as the Teacher’s advice regarding worship in Ecclesiastes 5, may we “draw near to listen rather than to offer the sacrifice of fools.”